- Home

- Carol McDougall

Wake The Stone Man

Wake The Stone Man Read online

wake

the

stone

man

wake

the

stone

man

a novel by

Carol McDougall

Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

Halifax & Winnipeg

Copyright © 2015 Carol McDougall

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, either living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Editing: Chris Benjamin & Brenda Conroy

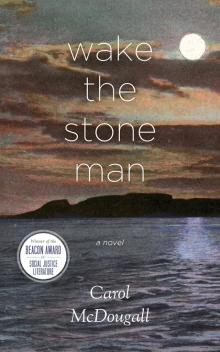

Cover image: Sleeping Giant, Fort William, Ontario Postcard

Design: John van der Woude

Printed and bound in Canada

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Published by Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

32 Oceanvista Lane, Black Point, Nova Scotia, b0j 1b0

and 748 Broadway Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, r3g 0x3

www.fernwoodpublishing.ca/roseway

Fernwood Publishing Company Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Nova Scotia Department of Tourism and Culture and the Province of Manitoba, through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, for our publishing program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McDougall, Carol, author

Wake the stone man / Carol McDougall.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55266-721-7 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-55266-764-4 (epub)

I. Title.

PS8625.D776W36 2015 C813’.6 C2015-900603-1

C2015-900604-X

For my family of friends.

Love is all there is.

book one

chapter one

The first time I saw her she was climbing over the top of the chain-link fence of the residential school. The tops of her fingers curled over the metal fence were dark, but the palms facing me were pink. Pink as mine. I wanted to look down at mine to check, but she was staring at me. I waited for her to speak. She didn’t.

I could have kept walking, should have kept walking down the path to the building where I took my ballet lessons. Didn’t have to stop just because she was staring at me. But I stopped and watched her.

“Nakina!” A flash of black behind her as a nun moved towards the fence. Black and white, and the glint of silver from the buckle of a belt. “Get off that fence.”

Thwack of metal as the buckle hit the fence.

I ran. I ran down the path, away from the residential school, ballet shoes bouncing off my back. I was on the other side of that fence and I didn’t have a strap coming down on my back but I ran like hell. She didn’t move.

After that day I looked for her. I wanted to ask her something. I wanted to ask her where she was going that day she tried to escape over the fence. Every time I went to my dance class I stopped outside the fence to see if I could find her.

Some people called St. Mary’s the residential school. My mom called it the orphanage. I asked her what it meant and she said it was a place for orphans, and I said what’s an orphan and she said someone whose parents are dead, and I said are all those Indian kids’ parents’ dead and she said no. I didn’t get it.

The place was huge. Bigger than the church and bigger than City Hall. A red brick building four storeys high, with rows and rows of narrow windows and a porch on the second floor. Indian kids lived there. Mostly Indian, looked like hundreds of them. And the nuns who ran the place were always yelling and making them line up. Nuns in long black robes screaming their heads off. Scary.

I stopped every time I walked by. I saw kids playing marbles under a statue of Jesus nailed to the cross. In winter I saw kids playing hockey on the rink they’d made in the field behind the school. In spring I saw kids working in the gardens and lining up to go in for mass when the bells in the chapel rang. But I didn’t see her.

***

The summer I was eleven everything changed. One minute I’m sitting on the dock, swinging my skinny little legs over the side, the next I’m standing up looking at the Sleeping Giant, thinking what the hell — what the hell am I doing here?

I looked back at the rust bleeding down the side of Sask. Pool 7. I looked at the fat rats waddling along the tracks beside the grain elevators. I looked at the thick green slime pouring out of the mill into the Kamanistiquia River. And it felt like I was looking at one of those ink blob pictures — first you see two faces nose-to-nose and suddenly you’re looking at a goddamned vase. Zap. I don’t know how the faces changed into a vase; all I know is after I saw the vase I couldn’t see the faces any more. One minute Fort McKay looked like home. Then zap, it looked like a hick town in the middle of the bush and I wanted out.

It was 1964 and stuff was happening out there, out past the Sleeping Giant across Lake Superior in the good ole U. S. of A. We watched it every night on the news. Martin Luther King had a dream; Kennedy got shot and bled all over his wife in the pillbox hat. Nice hat.

I remember my teacher running into the classroom screaming, “Our president’s been shot.” I don’t know what was weirder, that she thought he was our president or that I believed her. She told us all to go home, and I remember kids running down the halls screaming like there’d been a nuclear attack. Which, by the way, was another thing we were all freaking out about.

Things were happening. Every night on TV I watched guys getting blown up in Vietnam. I was learning new words like Viet Cong, Saigon, napalm bomb. One night we were eating barbequed hot dogs off TV tables and I watched this Buddhist monk tip a tin of gasoline over his head. He was sitting cross-legged on the road and whoosh, he went up in flames. Barbequed hot dog with barbequed monk. Stuff was happening out there. But I wasn’t out there. I was stuck in the middle of nowhere.

That day, when I was eleven, I waited on the wharf till my dad brought the boat around and we headed out through the breakwater past the lighthouse. The Merc engine kicked up a cold spray on my face. I looked back at the harbour as we pulled out and I could see the whole of Fort McKay broken down — North Fort and South Fort and the mountains. From out there you could see lines you couldn’t see in town. North Fort McKay. Money. Where my aunt and uncle lived and drank martinis with people like them who thought their shit didn’t stink. My Uncle Pete was such an asshole. Seriously, he was just a foreman at the mill but he thought he was the friggin Duke of Duluth. Everyone in North Fort McKay looked down on people who lived in South Fort McKay, who looked down on people who lived in West Fort McKay, where I lived. I lived in a cardboard-box house that looked just like all the other cardboard boxes on the street. They called them wartime houses, which made no sense to me because there wasn’t a war on, except for the Vietnam War, and I couldn’t see how my house had anything to do with that.

West Fort was bad, but it wasn’t the bottom of the barrel. The bottom of the barrel was the South Fort Reserve, on the other side of the swing bridge. Everyone crapped on them, but they had no one downwind of them to crap on.

I could see all that as the boat pulled away from the city out onto Lake Superior. My dad built the boat. He used to race hydroplanes but he couldn’t any more because he was a father and had responsibilities. Me. My mother made him give up racing so he built a nice little boat we could all toodle around in,

except when it was done it looked a lot like a hydroplane racer. Ha. Dad put a 75 Merc on the back of that thing and man could she go. Dad’s racing buddy Aho Sippo used to say, “That Merc really put the poop in ’er.”

It was sunny when we headed out. Dad didn’t bother to tell Mom we were going out because he thought we’d just do a spin past the Giant. But when we got near the Welcome Islands the sky went dark and the lake churned up fast. Superior did that. It would be calm as glass one minute then spitting up whitecaps the next. The sky went black, then lit up with forks of lightning. We were too far out when the storm hit to get into one of the bays along the shore. Dad shouted to me to get under the bow. The wind was blowing his curly red hair back off his face and his long body was curled over the engine. Dad kept a bunch of blankets and extra life jackets under the bow and I crawled into them like a nest. Couldn’t see anything, but I knew the waves were breaking high because the bow would dip down a few feet, smash and fly up again. The Merc was full throttle and the rain was pounding on the deck. I wasn’t scared. You’d think I’d be scared out there in a storm like that, but I wasn’t. Being stuffed under the deck was like being tucked safe inside a kangaroo pouch. I never worried because I knew no matter how rough it got my dad could ride it out.

The only thing the storm did was rock me to sleep, and when I woke up we were coming through the breakwater. It was dark. I could see the blinking of the lighthouse and the lights of a police boat following us in. Police were waiting on the dock. Mom called them when we didn’t come home. There were a lot of guys in uniforms and lights and questions, and I just wanted to go home and go to back to sleep.

At home Mom grabbed me and sobbed her face out. Then she started in on my dad. See, Mom was usually real quiet. Dad called her his rock because she was always so calm, so it was a big flippin deal when she lost it. She was standing in the kitchen beside a stack of dishes and she just picked one up and let fly. Dad ducked and it smashed against the wall behind him. She kept throwing plates. Dad kept ducking. I wondered why he didn’t get the heck out of the way. I guess he was like me — deer caught in the headlights. I wanted to know what it felt like to haul off and swing a plate across the room. Must have felt good. And bad. I didn’t ask. I went to bed.

That night I dreamt about waking the Stone Man — Nanna Bijou, the Sleeping Giant. I dreamt about him a lot. The Giant is a mountain of stone that sticks out into the harbour. Looks just like a man lying down with his arms crossed over his chest. When you grow up in Fort McKay the Giant gets under your skin and inside your head.

That night I dreamt I was standing on the wharf shouting my guts out across the harbour and there was this god-awful crash of rocks and the Stone Man sat up and looked at me, all surprised. And I threw my hands up and said, “What the hell!” I waited for him to say something profound but he just smiled and gave me a “Hey, how’s it going, eh?” sort of nod, then lay back down across the harbour and folded his arms across his chest.

***

I was a weird kid. Didn’t talk much, so people forgot I was there. When I was little people thought I was like Donny MacKellvey. He chased lawnmowers. As soon as someone on the street would pull the starter on a lawnmower Donny would be right there, watching like it was the Stanley Cup playoffs. People called Donny mongoloid, but I knew his family wasn’t from Mongolia. People used to think I was like Donny so they didn’t pay any attention when I was around. That was OK by me. I heard more that way.

I heard how Mr. Rutka crossed the dockworker’s picket line on purpose, and they said he was a scab and was going to pay for it. I heard how Mr. Abromovitch invited all the neighbours to his house on Christmas Eve so they could watch him kill his wife. He drove his car to our house to ask my dad to come over for a drink, which was nuts because he lived across the street. When my dad said he couldn’t go, Mr. Abromovitch left his car in our driveway because he was so drunk he didn’t remember driving over. His car was still at our house when the police took him away for shooting his wife. The bullet just grazed her ear so she wasn’t dead. Just stunned. But I always thought she was stunned. One of his sons came a few days later and got the car.

I used to go to church every Sunday morning with Mom and Dad. I’d go to Sunday school downstairs for the first half hour, then we’d go upstairs with our families for the church service. I liked church. I liked the smell of wood and wax. I liked the organ music and I could belt out the hymns with the best of them. I was sitting in church when I heard some men in the pew in front of me bragging about “taking care” of some guy on the reserve, and then they all laughed a lot. I didn’t know what they were talking about but I knew I didn’t like it — or them.

Someone stole my winter boots from the front vestibule when I was downstairs one Sunday. After that I stopped going to church. It was partly because of the boots, I mean, come on — how the heck can you say you’re a Christian and steal someone’s boots? But it was also the stuff I heard. I’d sit in the pew listening to all this stuff about what really went on, which didn’t sound anything like what the minister said was supposed to be going on, so I figured there was no god. Well at least not in Fort McKay. So I stopped going.

Instead I hung out in Paula Slobokin’s kitchen on Sundays while her baba made perogies and cabbage rolls and little pastry things she would make me eat because she said I was too skinny. She’d slap my hips and say “Wide hips. Lots of babies.” I hated that but I liked the perogies. Baba told us stories about the Ukraine, the old country, which was weird because my nana used to tell me stories about the old country, which she called Scotland, and Anna’s mummo called her old country Finland. When I was a kid I used to think the old country was on the other side of Mount McKay, and people wore kilts and had Ukrainian wedding ribbons in their hair and rode around on reindeer. Eventually I figured out there was no old country on the other side of the mountain — just trees, trees and more friggin trees.

On summer nights I’d sit out on the front steps with my mom and dad looking across at the neighbours who were sitting on their front steps looking across at us. Real exciting. Donny used to come over and sit with us. He never said much but I liked hanging out with Donny. You always knew where you stood with him. I’d sit there breathing in the rotten-egg sulfur stink of the mill, playing snakes and ladders with Donny and wondering what people in places like Toronto and Winnipeg and New York were doing.

I’d sit on the steps thinking about how I was going to get out of Fort McKay and wondering if everyone else sitting on their steps was thinking the same thing. Hard to tell. Seemed to me they were all pretty happy where they were. Reggie Dalmino’s dad worked at the mill and Reggie wanted to work at the mill. His twin brother Ace wanted to, you got it, work at the mill. The girls I hung out with sang skipping songs about who-am-I-going-to-marry and how-many-kids-am-I-going-to-have. Except in Fort McKay it was usually the other way around: how many kids am I going to have and is the bastard going to marry me? Aim high. But that was the thing. For most of my friends that was aiming high. There’s this saying here … good enough. When someone says “Hey, howya doing?” you say “goodnuff.” “See you at bingo next week.” “Goodnuff.” Life may not be great, but hey, it’s goodnuff.

But that summer I decided goodnuff wasn’t good enough for me. I wanted more. I wanted out. I kept thinking about the girl I’d seen trying to escape over the fence of the residential school. I figured she wanted out too.

chapter two

It was two years before I saw her again. I’d been sick the first week of high school so I had to go to the office to register. I was waiting outside the principal’s office feeling so nervous I thought I would puke, when she walked over, sat down beside me and said, “Hi,” just like that. Hadn’t seen her since the day she was trying to escape from the residential school, and she looked right at me and said “Hi” like we were best friends or something.

“Nakina Wabasoon?” The principal stuck his head out o

f his office. “Come on in.” After a couple of minutes the principal came back out and nodded to me.

“Molly Bell? Come in.”

I went in and sat down in a chair beside Nakina. The principal was short and fat and had a wonky eye so you never knew if he was looking at you.

He went through a lot of stuff about teachers and lockers and wings and periods and I kept nodding my head like an idiot. I was nodding and smiling and wondering which one of his eyes was the real one and which was the glass one, and I didn’t know what the hell he was saying.

Before we left his office he said to Nakina, “I see here on your file that you have epilepsy.”

“Yes.” She looked at me and I could tell she didn’t like him saying that in front of me.

“I’m going to set up an appointment for you to meet with the school nurse. You can let her know about your medication and give her your doctor’s name.”

“OK.”

“Oh, and Molly.”

“Yes?” I said.

“I want you to go with Nakina to the nurse. Since you’re in the same homeroom you’ll know what to do if she has a seizure.”

“OK.”

Outside the office door I turned to Nakina and said, “So, what’s epilepsy?”

“You’ll find out,” she said.

I was just about to tell Nakina that I didn’t have a clue where we were supposed to go and she said, “Follow me.”

So I followed her down the corridor. I followed her to our lockers. I followed her to our homeroom. And after that day, I just kept following Nakina.

We were both in Mrs. Kouie’s English class. English for girls in secretarial arts and cosmetology. Cosmetology — I remember getting real excited about that till I found out it had nothing to do with the theory of the universe.

I liked English. Liked books. Never told anyone but my favourite place was the Brodie Street Library. I used to sit at the table under a stained glass window with two big heads — Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare. I liked sitting with Charlie and Billy.

Wake The Stone Man

Wake The Stone Man